I've been playing video games for a very, very long time at this point. The first couple of times I stood in front of anything that resembled a game was back in 1979 or 1980. I don't recall which one it was now - might have been Asteroids. Might have been Space Invaders. All I know is that the moment my eyes took in that crude joystick and those round, red buttons of the arcade machine, I had found a kind of home. A hobby that has, so far, spanned a lifetime.

I dove headlong into that hobby.

And I played.

A lot.

As I got older, the hobby started shifting gears. Lives and high scores were replaced by crude plots, which gave way to interesting stories. These, in turn got more visceral and visual, becoming more thrilling by adding action into the already crowded gaming mix. Developers, you see, were no longer content to have just static pictures or wonderful text descriptions that conjured images far better than any computer generated graphics could ever be.

No. The developers started wanting to make statements about life, the universe and everything.

But the thing is, sometimes, when you encounter some of these games, you're young. You haven't seen much of life. So the stories - while perhaps complex and moving and interesting, only hit you on one level. Maybe it was a funny game - like a Sam and Max or a Monkey Island and there wasn't much more to it than the humour. Or maybe it was a Ultima 4 that did away with the bad guy as an adversary and instead took you on a journey toward self-fulfillment. [That, by the by, is a game structure that has very nearly never been replicated. And we are the poorer for it.]

But you didn't see the other levels of that game - the meaning behind the humour. Or the completely spiritual philosophy behind the concept of the Avatar. Maybe your head just wasn't in a place to appreciate any of that.

There are two games that exemplify this particular idea to me - two games that I played when I was much younger and so their plots and their ideas just sort of skated by me.

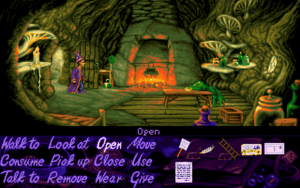

One of these was Simon the Sorcerer. There's not much to tell here, because I was a lot younger and so some of the more risque humour in that game just passed right over my head. I never truly understood how adult that game was underneath it's skin until I played it with my adult faculties in tow. And boy was I surprised, then.

The other game was something I picked up last year. I wanted to revisit it because it had been some twenty years since the first time I played it and - somewhere in the back of my head - it always had a kind of mystical pull. That game was The Dig.

The Dig is a lot of things in the LucasArts Pantheon Of Games. It's not a funny game. Yeah, there are funny lines, but at it's core, it's deeply serious. It's also not a particularly cartoony game. It trades in that particular style for something on the edge of nightfall - all reds and purples and blues - impossibly serene. This is quite an interesting design choice given that the backbone of the story is about being stranded somewhere hostile.

But mostly, it's about some very profound, incredibly thought-provoking topics - things that - by and large - don't show up in gaming. And if you're younger, well, it's all just fluff on top of an interesting science fiction story.

SPOILER WARNING. If you intend to play The Dig, please be aware that in order to write this post and have it make sense, I absolutely HAVE to spoil the plot of the game. Apologies in advance.

That profoundness stretches in all directions of the story. To whit: An asteroid is plummeting toward Earth. It's a collision course and there's not a lot Earth can do about it. As a last ditch effort, they try to blow it up so that the big chunk of space matter turns into smaller pieces of debris that won't do as much harm. While setting up to do just this, the away team discover that the Asteroid is really an alien spacecraft. It whisks the team off to parts unknown where the adventure really begins.

Once on the planet, the away team begins to explore, only to meet with misfortune when a crew-member dies. But here's where the game starts becoming philosophical: early on, it's discovered that there are crystals that can revive the dead. And so you do.

The philosophy of the game stems from this particular action. Is it the right thing to do? What does it mean to be alive in this state? How does it affect people? And - most importantly - why are the beings that built such a thing no longer alive today? All of these questions are answered - in due course - and as you're discovering the answers, you might find - especially as an adult - that the resolution of each problem - and the questions it provokes are not what you might have expected as a young person playing the game.

There's one other thing going on in The Dig that you might not notice as a younger person: the colour scheme and the slow pace of the game are both incredibly restful. It's like a little zen oasis, seeing each particular landscape drenched in those particular colours and being involved in this slowly unfurling mystery.

I can - quite safely - say that the younger me would never have picked up on much of this. You see, I hadn't had time to think about life and death and how profound that one special span of time is.

haha I remember playing breakout, and what’s weird is that very basic objective of ‘don’t miss the ball’ is still very entertaining.

I don’t think I ever played Simon the Sorcerer or The Dig, I was kind of late to the PC game. I built my first one in 1996 I think it was. A Cyrix 166 with 64 megs or ram and two 1gb hard drives running windows 95. And it cost me something like $2000. That was before accelerated graphics and I was just happy it could run games like Doom and Rise of the Triad. When Quake came to the scene that changed everything, within the year 3DFX was making a dedicated gpu and it made everything -amazing- then the race was on for more processing power and storage etc.

I remember around ’98 or 99 when the gigahertz barrier was finally breached and everyone was saying ‘That’s as far as we’ll ever get’ and ‘Architecture will never be able to support more than that’. And here I am with my 3.3gz 6 core processor, and it’s old now.

Anyway, derailed a bit there :) but I suppose the overlying point is that things have definitely changed.

Thanks Grey…I’ve played neither. Added to my gog wishlist of Eternal Backloggedness.